I like Wednesdays. There are just seven pupils that I see twice a week, and they arrive, in a 3 and then a 4, on Wednesdays. When this “second lesson” was instigated, I tried just NOT planning anything, but to allow them to use it as a workshop to air their particular struggles with Maths. Today was unusual because there is a lot of illness in school at the moment so I just had Guy* and Becky*. On the way to the lesson….

Guy (jumping and landing a quarter turn around) We did 90 degrees today.

Oh yes, what happened?

We did (jumping some more) 90, 180, jump jump….

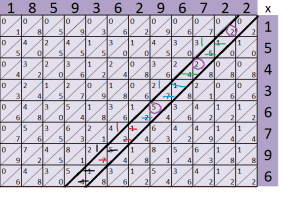

partial 90x table

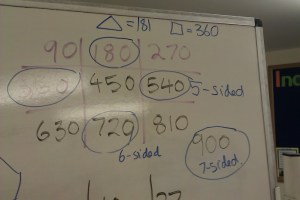

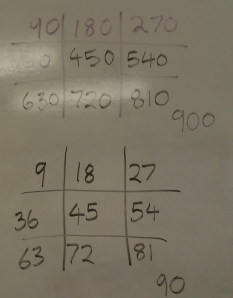

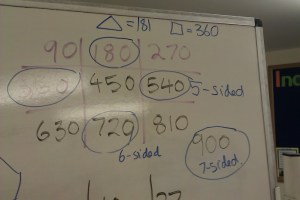

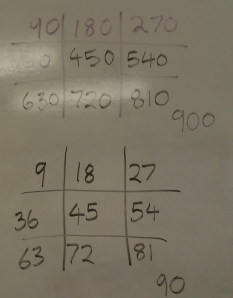

We had arrived in our teaching room by now, so I wrote up 90, 180 on the board. Thanks to Jan Poustie’s brilliant work on Dyscalculia**, I ALWAYS (and there’s not many things I’m strict about in lessons) write tables in a 3×3 grid. Poustie’s theory is that this makes them easier to memorise and recall, for kids who struggle to learn them. I’ve worked like that for 3 years now and there is more, so much more to it than that, but that’s for another blog post. So, anyway, up on the board goes 90, 180, and they supply 270, 360 and then get stuck. I asked them, did they stop there? Yes, that’s all the way round. But the table has 5 empty slots in it… what next? What does it look like?

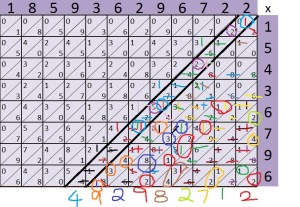

Becky “It looks like the 9x table” .

90x and 9x table, in a 3×3 grid ref Jan Poustie

OK you can trust that, let’s write up the 9x table (Lots of OOhs and Aahs favourite table because of the pattern in it, and because it also works so beautifully on your fingers). So up goes the 9x table with them providing all the numbers correctly. Back to the 90x table, it’s easy now cos we’ve got the 9x table as a crib…

So I volunteer to do the jumping bit if they chant…. 90, 180, 270, 360, 450, 540, 630, 720, 810, 900… now the room is gently spinning and I am facing away from the students. They seem to think this is hilarious, note to self, get a pupil to do this next time so I can be the one laughing…

But still this feeling that the angles above 360 don’t mean anything. They agree (me jumping more gently this time) that it makes more sense to say 90,180,270,360,90,180,270,360….

One of the best decisions I made this term was to keep a big box of STUFF at school, this is what enables me to teach these drop-of-a-hat lessons when the kids provide a topic. For me, the REALLY interesting sequence is 180,360,540,720… and later, when enough of the boys have got hooked on skateboarding, this will be a beloved sequence for them too, but they’re a bit young yet.

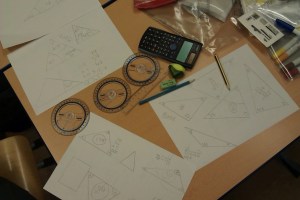

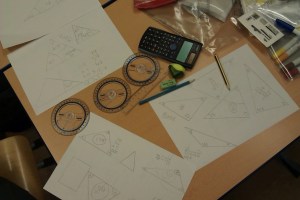

I draw an equilateral triangle on the board (we worked a lot with triangles last week, and I discovered that for all of them, this is THE triangle). They could tell me that all the sides would be the same length, but no idea about the size of one angle (90? 45? 25?) so we set up a little production line, drawing triangles, measuring the angles and adding them together. They knew (from last week) how HARD it is to draw an equilateral triangle by eye, so we settled on any triangle, as odd and different as you like. The numbers started to mount up. 196, 181, 180… for me, the tension was mounting. It is SOO tempting to correct and reject outliers, and this wasn’t looking promising. But holding my hair on, I reminded myself that a small group is an ideal venue for measuring angles, cos protractors can get a bit of reputation for being tricky customers to use, and by Year 9 or 10, some kids have got themselves REALLY confused. Even if The Sequence didn’t emerge, they would gain a lot of confidence measuring angles.

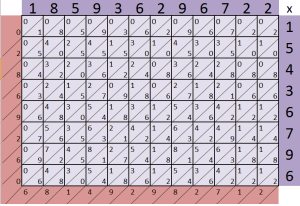

How to measure an angle using a protractor

It took me a lot of trial and error to work this one out. Kids really get confused over WHAT they are measuring, so I start by reminding them how they find the length of a line using a ruler. One end of the line sits under the zero, the other end of the line gives you the answer. I bring the ruler near the protractor and show them that the protractor is just a little round ruler – the degrees are almost 1mm wide. I draw the angle in, running the pencil around the edge of the protractor, and show them they are measuring the curve, and it is … degrees. Becky just needed reminding once that the centre of the protractor MUST be on the corner of the triangle, otherwise the answer is wrong. They drew the big curves on to the first few triangles. It looked a bit odd, and we discussed it, but later they dropped that and just measured the angles.

It took me a lot of trial and error to work this one out. Kids really get confused over WHAT they are measuring, so I start by reminding them how they find the length of a line using a ruler. One end of the line sits under the zero, the other end of the line gives you the answer. I bring the ruler near the protractor and show them that the protractor is just a little round ruler – the degrees are almost 1mm wide. I draw the angle in, running the pencil around the edge of the protractor, and show them they are measuring the curve, and it is … degrees. Becky just needed reminding once that the centre of the protractor MUST be on the corner of the triangle, otherwise the answer is wrong. They drew the big curves on to the first few triangles. It looked a bit odd, and we discussed it, but later they dropped that and just measured the angles.

Fairly quickly we had 10 results and I asked for comments. Becky thought all the numbers were pretty close together, but lots of different ones. I confessed that the 196 at the beginning did look a bit odd, and checked the triangle – a mistake had been made and they were happy to change the result to 182.

So we had a variety of different results, I suggested we find a mean average (I could see it would work out how, but it seemed sensible to summarise the data). They thought they could do it… but after a crash revision of means, becky added them all, and got 1812, divided by 10 and got 181.2.

This, frustratingly, drew a blank and our half hour was nearly up but I had mentioned that task 2 would the the same, with 4-sided shapes, and they begged an extra 5 minutes. We rapidly found 254, 366, 360 and 360, and since Guy had intended to draw a rectangle, he was adamant that his 360 was “right”. The mean average (worked out unassisted by Becky) was 360. Another blank.

So, I write them up near the 90x table on the board. Becky gets that lightbulb look on her face:

Well the “2” is a bit wrong on 182, but the 360 is in the table and so is 180…?

I allowed that we might make little mistakes and they got really excited about the idea that every other number in the table was appearing, the next one, for 5-sided shapes, could be 540, then 720 for 6-sided shapes….

35 minutes into a 30 minute session the time had REALLY come to throw them out of the door. After half term, we will draw and measure 5- and 6-sided shapes.

* Names changed, always!!

** Jan Poustie, 1990, Mathematical Solutions – an introduction to Dyscalculia Part B How to teach children and adults who have Specific Learning Difficulties in mathematics Available direct from the author’s website

It took me a lot of trial and error to work this one out. Kids really get confused over WHAT they are measuring, so I start by reminding them how they find the length of a line using a ruler. One end of the line sits under the zero, the other end of the line gives you the answer. I bring the ruler near the protractor and show them that the protractor is just a little round ruler – the degrees are almost 1mm wide. I draw the angle in, running the pencil around the edge of the protractor, and show them they are measuring the curve, and it is … degrees. Becky just needed reminding once that the centre of the protractor MUST be on the corner of the triangle, otherwise the answer is wrong. They drew the big curves on to the first few triangles. It looked a bit odd, and we discussed it, but later they dropped that and just measured the angles.

It took me a lot of trial and error to work this one out. Kids really get confused over WHAT they are measuring, so I start by reminding them how they find the length of a line using a ruler. One end of the line sits under the zero, the other end of the line gives you the answer. I bring the ruler near the protractor and show them that the protractor is just a little round ruler – the degrees are almost 1mm wide. I draw the angle in, running the pencil around the edge of the protractor, and show them they are measuring the curve, and it is … degrees. Becky just needed reminding once that the centre of the protractor MUST be on the corner of the triangle, otherwise the answer is wrong. They drew the big curves on to the first few triangles. It looked a bit odd, and we discussed it, but later they dropped that and just measured the angles.