Click an image below to see it full screen then print it out.

Click an image below to see it full screen then print it out.

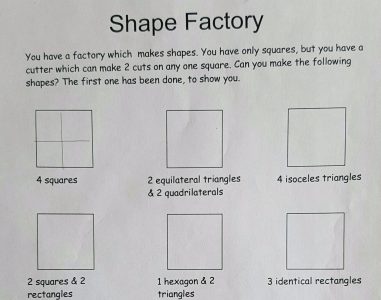

Puzzle to interest students in the rather dry subject of the names of shapes. Part A free-form, Part B, aiming for specific shapes.

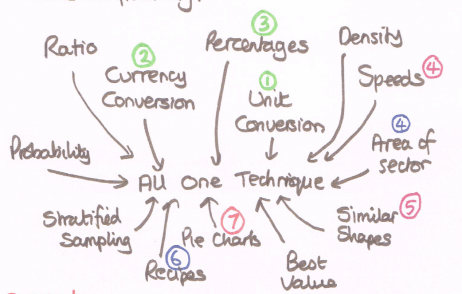

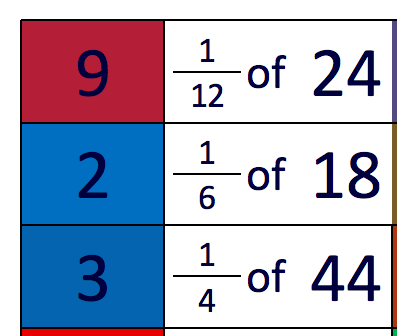

I invented “Ratio Grids” to help students who struggle with Proportional Reasoning. The philosophy includes:

These work best if they are printed onto card, laminated, then cut up. To play, shuffle them, place them face up, and pick an easy question. Find the answer to that question, chain that card on, repeat…

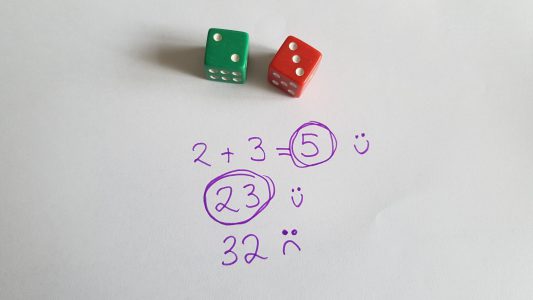

2 dice and a pen and paper.

The person who has the most points.

This sample space diagram may help:

|

Sample Space Diagram for 2 Dice |

||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

1 |

(1,1) |

(2,1) |

(3,1) |

(4,1) |

(5,1) |

(6,1) |

|

2 |

(1,2) |

(2,2) |

(3,2) |

(4,2) |

(5,2) |

(6,2) |

|

3 |

(1,3) |

(2,3) |

(3,3) |

(4,3) |

(5,3) |

(6,3) |

|

4 |

(1,4) |

(2,4) |

(3,4) |

(4,4) |

(5,4) |

(6,4) |

|

5 |

(1,5) |

(2,5) |

(3,5) |

(4,5) |

(5,5) |

(6,5) |

|

6 |

(1,6) |

(2,6) |

(3,6) |

(4,6) |

(5,6) |

(6,6) |

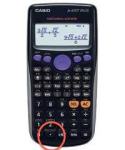

On the CASIO fx-83gt PLUS factorising is done like this:

This is a natural way to introduce what indices mean, because the CASIO gives the answers in index form eg 34 rather than 3x3x3x3

CASIO calculators have a very useful function of generating random numbers. Left to their own devices, they will choose a number between 0 and 1, with 3 decimal places. If you want a WHOLE NUMBER then you need to type 1000 Shift Ran# then press the equals button = . Here is a quick (silent) film showing you how to do it.

CASIO calculators have a very useful function of generating random numbers. Left to their own devices, they will choose a number between 0 and 1, with 3 decimal places. If you want a WHOLE NUMBER then you need to type 1000 Shift Ran# then press the equals button = . Here is a quick (silent) film showing you how to do it.

A word about Dyscalculia and Dyslexia

According to Brian Butterworth, Dyscalculia is a severe lack of awareness of number, coupled with great difficulty in performing arithmetic tasks. Research and Diagnosis in the UK is still at a relatively early stage, I can recommend the writing of Jan Poustie (herself a sufferer) as an excellent start for the reader wishing to be able to “see the world through Dyscalculic eyes”, and for practical suggestions of how to cope. ** the best book – Mathematical Solutions Part B is available from the author (see comment below)

Butterworth suggests that about 4% of the population may “have dyscalculia”. Looking at the bigger picture, it is clear to anyone working with maths education that a far larger proportion of the population struggle with aspects of Maths, and do not thrive on the traditional approach.

I prefer to see “number blindness” as a spectrum, on which some people are extremely fluent and comfortable with number, to the extent that they seem truly gifted, others struggle painfully, and the majority are somewhere in between, often feeling that they are worse than average, even if they in fact are right in the middle. I start work with every student assuming that they are “number-blind” until I see evidence to the contrary. This helps me to remember that, compared with a Maths teacher, most people are relatively number-blind. Unless you immerse yourself in number as much as a teacher probably has, you may not recognise high powers of two, multiples of large primes like 17, etc etc.

Many Dyslexics struggle with Maths, perhaps because of the extremely complicated processes required to carry out the high-end of arithmetic operations, such as pen and paper division. I am privileged to have worked with a handful of severely dyslexic students, who were very articulate about their learning styles and helped me to experiment with how to express Mathematical reasoning in a way that they could make sense of. Poustie indicates that individuals may well be experiencing some degree of Dyslexia and Dyscalculia, together.

Labels such as Dyslexia and Dyscalculia are only helpful if you have some strategies for coping with them, and I tend to focus on the learner, the Maths, and the strategies, and not worry too much about labels.

I welcome feedback, please use the reply box.

I set this problem today, during a lesson in which we had been looking at simultaneous equations with 2 unknowns:

A + B = 92

A + c = 57

B + C = 59

M came up with this answer:

POSTSCRIPT –

M then set me this problem:

A-B = 25

B+C = 151

A+C = 176

which turned out to have an unexpected twist in it….. Have fun!

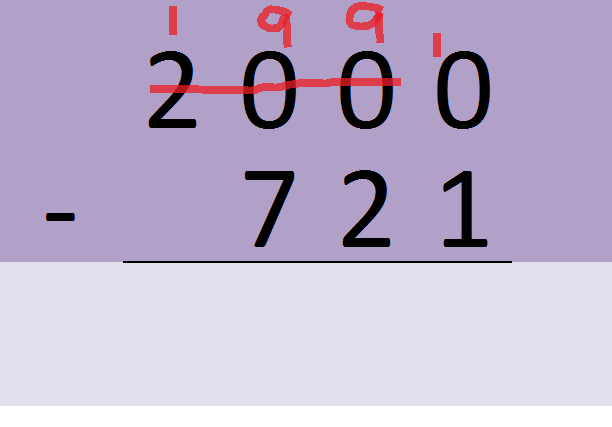

Do any of your students get in a mess with “double borrowing”? There’s a very simple solution which builds on their existing knowledge of subtraction with borrowing….

There is a very simple solution to this, encourage the student to look at the number differently. Borrow ONCE from the “200” on the top, which becomes 199.

Borrow ONCE from the “200” in the top number – now this sum is ready to do, and there’s far less that can go wrong.

Try it on a student near you, and use the reply box to tell readers what happened next!